Medical branches / Pathology: symptoms

lat. -

| Definition | [hide] |

| 1. Etymology | [show] |

Word family: a derivative of the verb ψύχω. The guttural stem ψυγ- and the productive ending -μός (on which see CHANTRAINE 1933: 133-6, esp. 135-6, § 103). Cognates in medicine: fem. noun ψύξις, neutr. noun. ψύγμα, comp. masc. noun ψυγμοκατάρρους, adj. ψυχρός and ψυκτικός.

Medical nouns in –mos: agmos ”fracture”, nugmos ”pricking sensation, irritation” etc.

| 2. General linguistic commentary | [show] |

The most attested form in literary and medical sources is χύτρα, even if also κύθρα counts several occurrences. On the contrary, the last one is extremely rare in the inscriptions[5], whereas it becomes overwhelming in the papyri, especially from the I century CE.

The word is very productive and originates many derivatives and compounds. Among them only the following ones occur in medical texts. Some diminutive forms: χυτρίδιον, formed by the widespread suffix -ίδιον[6], significantly attested (41 occurrences), with the graphic alternatives κυθρίδιον (6 occurrences), χυθρίδιον (3 occurrences) and κυτρίδιον (2 occurrences); χυτρίς (3 occurrences)[7]; χυτρίον (1 occurrence) and κυτρίον (1 occurrence)[8]; whereas χυτρίσκη[9], found in Fr. Alch. 30,12 (I 119,21 Halleux), i.e. P.Holm. 6,28 εἰ⟨ς⟩ χυτρίσκιν (l. χυτρίσκην), never occurs in medical writers. Neither compounds nor adjective formations (χυτραῖος, χύτρειος, χυτρεοῦς, χυτρικός, «of earthenware»)[10] are attested, with the only exception of χύτρινος[11] in the aforementioned substantivized form.

No trace of the word in Coptic, since nouns like ϣιω[12] are semantically equivalent but with no phonetic connection with it. On the contrary, the term has kept a lexical and functional continuity in modern Greek, as it indicates a ceramic or metal kitchen σκεῦος[13], especially the pressure cooker, emblematically called χύτρα ταχύτητας, for it reduces the cooking time of food.

| 3. Abbreviation(s) in the papyri | [show] |

| B. Testimonia | [show] |

List of testimonia

Diocl. Fr. 183a.39-55 (Paul Aeg. Epit. Med. I 100.3 = CMG IX.1, 69-70 Heiberg); Dsc. V 11; P.Oxy. Hels. 46.15-19; P.Oxy. LXXIII 4959.3-10; Gal. Simpl. med. temp. ac facult. 11.518-520 K.; Gal. Comp. med. sec. loc. 13.353 K.; Hdn. Pros.Cath. vol. 3.1, p. 166; Hdn. Pros.Il. vol. 3.2, p. 115; Poll. IV 186; Vett.Val. II 41 & IV.20; ps.Gal. Progn. de decub. ex math. scient. 11 (= 19.562 K.); De herb. 91-94; Eutecn. Paraphr. in Nicand. Alexiph. 16; Orib. Coll. Med. VIII 24.17; Orib. Syn. ad Eust. I 19.7-8; Man. 2.443, 3.276; Heph. Astr. in Cat. Cod. Astrol. p. 224 & 264; ps.Mac. Serm. 7.7; Aet. Iatr. II 3; Rhet. Cap. Selecta p. 155; Paul. Aeg. Epit. Med. I 100.3 (CMG IX.1, 69-70 Heiberg = Diocl. Fr. 183a.39-55); Hippiatr. Cantabr. 30.2, 49.3, 87; Hippiatr. Paris. 461, 837, 1021, 1082; Hippiatr. Berol. 130.78; Add. Lond. ad Hippiatr. Cantabr. 52; Suda 1085 Adler s.v. μινθώσομεν; Astrol. cod. Vet. Marc. 335 Vol. II, p. 189; Schol. Ar. Plut. 313; Schol. Hom. Il. 20.485; Schol. in Nic. Ther. 43.

Select testimonia in translation

1. Diocl. Fr. 183a.39-55 van der Eijk (cited in Paul Aeg. Epit. Med. I 100.3 = CMG IX.1, 69-70 Heiberg)

ὅταν δέ τι περὶ τὸν θώρακα μέλλῃ γίγνεσθαι, τούτων τι προσημαίνειν εἴωθεν· ἱδρὼς ἐπιγίγνεται εἰς ὅλον τὸ σῶμα καὶ τὸν θώρακα, καὶ τὴν γλῶτταν παχεῖαν ἔχειν· πτύουσιν ἁλυκὰ ἢ πικρὰ ἢ χολώδη· ὑπὸ τὰς πλευρὰς ἢ ὠμοπλάτας ἀλγήματα γίγνεσθαι δίχα προφάσεως, χάσμαι συνεχεῖς, ἀγρυπνίαι, πνιγμοί, δίψος ἐξ ὕπνου, ἀηδῶς ἔχειν τὴν ψυχήν, ψυγμοὶ στήθους καὶ βραχιόνων, χειρῶν τρόμος, βῆχες ξηραί. (...) τοῖς δὲ καταφρονοῦσι τῶν τοιούτων σημείων τάδε εἴωθεν ἐπιγίγνεσθαι τὰ ἀρρωστήματα· πλευρῖτις, περιπνευμονία, μελαγχολία, πυρετοὶ ὀξεῖς, φρενῖτις, λήθαργος, καῦσος λυγμώδης.

“When a condition is about to develop in the chest, one of these signs forewarn of it: sweat in the entire body and chest, and swollen tongue; salty, bitter or bilious spit; pain without obvious cause below the ribs or the shoulder blades; continuous yawning; sleeplessness; choking; thirst upon waking; disgust; freezing of the chest and arms; trembling of the hands; dry coughs. (...) The following ailments attack those who ignore this sort of signs: pleurisy, inflammation of the lungs, atrabiliousness, acute fever, phrenitis, lethargy, or burning fever attended with hiccup.” 2. Dsc. V 11. See also ps.Dsc. Ther. 4

θαλάττιον ὕδωρ δριμύ, θερμαντικόν, κακοστόμαχον, κοιλίας ταρακτικόν, ἄγον φλέγμα. θερμὸν δὲ καταντλούμενον ἐπισπᾶται καὶ διαφορεῖ, ἁρμόζον τοῖς περὶ νεῦρα πάθεσι (...)· διαφορεῖ καὶ πελιώματα πυριώμενον, καὶ πρὸς τὰ τῶν θηρίων δήγματα, ὅσα τρόμους καὶ ψυγμοὺς ἐπιφέρει, μάλιστα δὲ σκορπίων καὶ φαλαγγίων καὶ ἀσπίδων (...)

“Sea water: it is pungent, warming, sets the stomach and the bowels in motion, and incites phlegm. Warm water poured over is absorbed and dissipates, being suitable for the affections of the nerves/sinews (...).It also dissipates the livid spots, used for vapour baths, and is used against bites of beasts, those which cause shivering and chilling/ rigour, mostly the bites of scorpions, spiders and asps (...)” 3. Ruf. περὶ κλυσμάτων (cited in Orib. Coll. Med. VIII 24.17 = CMG VI 1.1, p. 272 Raeder)

καὶ ἔλαιον δ’ ἐπὶ πάσης φλεγμονῆς καθ’ ἑαυτὸ ἁρμόζει ἐνιέμενον, καὶ ἐφ’ ὧν ἀσθένεια περὶ τοὺς τόπους ἐστί, καὶ ἐφ’ ὧν γίνονται στρόφοι· διαλυτικώτερον δὲ μᾶλλον τῶν πνευμάτων ἐστί, πηγάνου ἡψημένου <ἐν> αὐτῷ ἢ κυμίνου ἢ ἀνήθου ἢ δαφνίδων, ὅτε καὶ τοῖς ἀπὸ ψυγμῶν πυρέσσουσιν ἁρμόζει.

"Oil, infused, is suitable for every kind of inflammation, in cases of localised feebleness as well as in cases of colic. For it dispels flatulence when rue or cumin or dill or laurel has been cooked in it, being also suitable for feverish patients having a chill". 4. P.Oxy. Hels. 46.15-19 (I/II) Business letter

οὐ γὰρ ἠδυνήθην ἐπὶ τοῦ| παρόντος γράψαι οὐδενὶ διὰ τὸ ἀπὸ| νόσου ἀνα̣λαμ̣βάνειν καὶ ψυγμοῦ| μεγάλου. καὶ μόγις ἠδυνήθη(ν) καὶ ταῦ|τα γράψαι β̣ασαν̣ιζ[ό]μεν̣ο̣ς

“I have not been able to write to anyone on the present matter because I am recovering from an ailment and a great cold. Even this I have been able to write with difficulty being in torment ...”

5.

P.Oxy. LXXIII

4959.3-10 (II) Letter of Ammonius to his parents regarding the health

of his

brother, Theon (other trasl.: ed.pr.;

Arzt-Grabner & Kreinecker, Light from

the East 2010, 22f.)

ἐξήρκει

μὲν καὶ

τὰ Θέωνος τοῦ ἀδελφοῦ γράμματα| διʼ ὧν ὑμεῖν (l. ὑμῖν) ἐδήλου ὅτι

ψυγμῶι

ληφθεὶς

ἐκ | βάθους καὶ ἐκλύ̣σει τοῦ σώματος〚καὶ̣〛ἐν ἀγωνίαι

ποι|ήσας πάντας ἡμᾶς οὐ τῆι τυχούσηι, διὰ τοὺς θε|οὺς αὐτῆς ὥρας

ἀνέλαβεν καὶ

τέλεον ἀνεκτήσα|το, ὥστε καὶ λούσασθαι αὐτῆς ἐκ̣ε̣ίνης τῆς ἡμέ|ρας καὶ

μηδὲν ἔτι̣

α̣ὐ̣τ̣ῶι τοῦ σ̣υ̣μβάντος ἐνκατά|λειμμα (l. ἐγκατάλειμμα) εἶναι.

“The

letter of

my brother Theon has hopefully been sufficient to let you know that

having been

seized by a chill arising deep inside and by bodily feebleness –

something

which caused us all a good deal of anxiety – with the help of the gods

he

recovered instantly and was totally restored so that he could even take

a bath

in that very same day and that no trace of what happened to him has

remained.”

6. Gal.

Simpl. med. temp. ac facult. II 20-21 (11.518-520

K.)

οὔτε γὰρ

ἁπλῶς εἰ θερμὸν,

ἢ ψυχρὸν, ἢ ξηρὸν, ἢ ὑγρόν ἐστιν ἕκαστον

τῶν φαρμάκων ζητοῦμεν (...), ἀλλ’ ὅπως ἔχει πρὸς ἀνθρώπινον σῶμα. (...)

πῶς μὲν

οὖν ἄν τις ἔλαιον ἐργάζηται τοιοῦτον λέλεκται καὶ πρόσθεν· πῶς δ’ ἄν

τις ἁπλῷ

νοσήματι προσφέροι, νῦν εἰρήσεται, τοσοῦτον ἀναμνησάντων ἡμῶν

πρότερον, ὡς ἐν ταῖς τῶν νοσημάτων

διαφοραῖς ἐδείκνυτο, τινὰ μὲν ἐπὶ τὸ θερμότερον

ἐκτετράφθαι σώματα χωρὶς κακοχυμίας τινὸς ἢ στήθους ἢ σπλάγχνου

φλεγμονῆς,

ὥσπερ ἐν ταῖς σφοδραῖς ἐγκαύσεσιν εἴωθεν γίγνεσθαι, τινὰ δὲ ἐπὶ τὸ

ψυχρότερον,

ὡς ἐν τοῖς καλουμένοις ἤδη συνήθως ὑπὸ πάντων

ἀνθρώπων ψυγμοῖς. ἐν δὴ ταῖς τοιαύταις διαθέσεσιν ἔλαιον προσφέρων

ἐξευρήσεις

ἐναργῶς εἴτε θερμαίνειν ἡμᾶς πέφυκεν εἴτε καὶ ψύχειν.

(...)|| τοῖς

ἐψυγμένοις δὲ σαφῶς οὐδὲν εἰς ὠφέλειαν ἢ βλάβος ἐξ ἐλαίου χρίσεως

ἀποβαίνει. ᾧ

καὶ δῆλον ὡς εἰ καὶ θερμαίνειν ἡμᾶς πέφυκεν, ἀλλ’ οὐκ ἔτι γε σφοδρῶς ἢ

ἐναργῶς,

ὥσπερ ῥητίνη καὶ πίττα καὶ ἄσφαλτος.

“For we

do not simply

investigate whether a medicament belongs to the warm, cold, dry or

moist ones

(...), but how it interacts with the human body (...) I have already

spoken of

how oil is to be prepared. I will now explain how it should be applied

in cases

of simple affections after a brief reminder that, as it has been

demonstrated

in the section/work concerning the differences between diseases, some

bodies

have grown with a greater tendency to warmth (unless the humours are in

an

unhealthy state or there is an inflammation of the chest or the spleen)

as in

cases of acute burning fits, while others are more inclined towards

chilliness,

as in cases of the affections nowadays commonly called chills

(psygmoi).

If oil is offered to the

patient in one of these conditions, one will find out clearly whether

it is its

nature to warm us up or to cool us down (psychein).

(...) whereas for the persons affected by a chill no clear benefit or

damage is

to be observed when oil is smeared on. This indicates that, although

its nature

is to warm us up, it does not effect this to a great degree or clearly

as do

resin, pitch and bitumen.”

7. Gal.

Comp. med. sec. loc. 20.2 (13.353 K.)

πρὸς

ἰσχιάδας καὶ ψυγμοὺς

Ὑγιεινοῦ Ἱππάρχου· βοτάνην Ἰβηρίδα, ἥν τινες καλοῦσι λεπίδιον ἢ

ἀγριοκάρδαμον,

ἀνελόμενος τὴν ῥίζαν αὐτῆς κόψον καὶ στέατι χοιρείῳ συμμαλάξας εἰς

τρόπον

ἐμπλάσματος ἐπιτίθει κατὰ τοῦ ἀλγοῦντος τόπου ἐπὶ ὥρας τρεῖς, εἶτα

πέμπε εἰς

βαλα||νεῖον. (...)

“Against

ischias

and muscular stiffness, of (Hygieinus?) Hipparchus: dig up the root of

pepperwort, called by some lepidion or wild cardamum, cut it, work it

into a

plaster by softening it together with pig’s suet and apply on the

aching part

for three hours. Send then the patient to a bath-house ...”

8.

Pollux IV 186 (256 Bethe)

(...) φρίκη, ψυγμός ψῦξις, [φρίξ FS],

[[φρίττειν A], ἐψῦχθαι κατεψῦχθαι BC]],

ῥῖγος, ἠπίαλος. (...)

9.

Vett. Val.

4.20

Κρόνος

Ἀφροδίτῃ (...) οἱ δὲ καὶ ἐπιβουλεύονται ἢ φαρμάκων πεῖραν λαμβάνουσιν

καὶ τῶν

ἐντὸς ὀχλήσεις ὑπομένουσιν, ἀσθενείαις τε καὶ ψυγμοῖς καὶ ῥευμάτων

ἐπιφοραῖς περιπίπτουσι

When

Cronus is in Aphrodite some (...), while others are targets of plots,

are

receive a taste of drugs/poison, suffer internal discomforts or fall

into

weakness, chills or rheumy dicharges (...)

10.

De Herb. 92-94

κισσίον

τόδε

πάντες ἐπὶ χθόνα ναιετάοντες

ἄνθρωποι

κλῄζουσι λελίσφακον, οἱ δέ τε θεῖον.

λύει

γὰρ

ψυγμὸν κακοτέρμονα βῆχά τ’ ἀνιγρήν

Kission,

called lelisphakos by all people on earth,

while some qualify it as theion. For

it dispels the cold, which ends with difficulty (or: badly), and the

burdensome

cough.

11.

Eutechn. Paraphr. in Nic. Alex. 16 Geymonat

μήκωνος

δὲ τῆς ἐν κεφαλῇ φερούσης

τὸ σπέρμα οἱ τοῦ ὀποῦ πεπωκότες

πάσχουσι τοιάδε· καθυπνοῦσι πολλά,

ἔπεισι τὰ ἄρθρα αὐτῶν ψυγμός, τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς κεκλεισμένους ἔχουσι,

ἱδροῦσιν

ἀθρόον καὶ δυσῶδες (...)

Those

who have drunk the juice of the poppy, the seeds of which are in its

head,

suffer the following: they sleep long, chill develops in their limps,

they keep

their eyes shut and their sweat is profuse and smelly.

12. Orib. Coll. Med. VIII 24.17 (CMG VI 1.1, p. 272 Raeder, Rufus of Ephesus). See also Syn. ad Eust. I 19.8, see [3]

13.

ps. Macar. Serm. 7.17

ὥσπερ

γὰρ τὴν εἰκόνα τοῦ

σώματος πάντες μὲν ἔχουσιν, ἀλλ’ οἱ μὲν ὑγιῆ καὶ ἀσινῆ αὐτὴν κέκτηνται,

οἱ δὲ

νοσερὰν ἢ καὶ τετραυματισμένην. ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐν αὐτοῖς τοῖς πάθεσιν τοῦ

σώματος

πολλή τις διαφορὰ τυγχάνει· οἱ μὲν γὰρ προφανῶς τραύματα ἔχοντες

ἀλγοῦσιν, οἱ

δὲ τραύματα πρόδηλα μὴ ἔχοντες ψυγμὸν δεινὸν ἐν τῷ σώματι ἔχουσιν ὥστε

μηδὲ κινεῖσθαι δύνασθαι καὶ κατὰ

μὲν τὸ ὁρώμενον ὡς ὑγιὲς εἶναι δοκεῖ τὸ σῶμα, κατὰ δὲ τοὺς πόνους καὶ

τὴν

κίνησιν τῆς ἐργασίας πολὺ χεῖρον αὐτοῦ ἐστι καὶ δυσθεράπευτον πάθος τοῦ

προδήλως πεπληγμένου.

Everyone

has a visible physical body ― some a healthy and intact one, some an

ailing

body or a body with wounds. But the affections of the body exhibit

great

differences. For persons with evident wounds are in pain, while others

lack these

but suffer from severe stiffness, so that they are not able to move.

And

outwardly the body seems healthy, but when it comes to labour and

movement in

connection with work its suffering is much worse and more difficult to

treat

than that of the body which has visible wounds.

14a.

Hippiatr. Paris. 1021

πρὸς

ἀναφορὰν καὶ μυκτήρων κάθαρσιν. Ῥέφανον

παναρίαν συντρίψεις. ἐὰν ἀπὸ ψυγμοῦ τοὺς ῥώθωνας αὐτοῦ θέλῃς καθαρίσαι,

λάβε

γάρου κυάθους γʹ καὶ ἐλαίου κύαθον αʹ καὶ εἰς τοὺς ῥώθωνας κατὰ βʹ

κυάθους ἔνθες,

καὶ πατείτω. εἶτα εἰς παραπόδισμα

αὐτὸν βάλε καὶ σύνδησον καὶ ἔασον αὐτοῦ

κατέρχεσθαι τὸ προέκρευμα ἀπὸ τῶν ῥωθώνων.

To

promote exhalation and

cleanse the nostrils. Pound a cabbage. If you wish to cleanse his

nostrils of a

cold, take three cups of fish-sauce and one cup of oil. Pour two cups

in each

nostril, and press. Then bind the animal in the stable and leave them

so that

the fluid excretion runs out of the nostrils.

14b.

Hippiatr. Cantabr. 49.3

πρὸς

δὲ τὴν τοῦ ψυγμοῦ κύπρινον διὰ ῥινῶν δίδου χρίσμασί τε

θερμαντικοῖς χρῶ καὶ χαλαστικοῖς ...

To

end

the cold fit administer henna-oil nasally and use warming and relaxing

unguents.

14c.

Hippiatr. Paris. 837

ἄκοπον

θερμαντικὸν τὸ παρὰ Χαρίτωνος, ποιεῖ νεφριτικοῖς, σχιακοῖς, παρετικοῖς

καὶ πᾶσι τοῖς ἀπὸ ψυγμοῦ τι πάσχουσιν.

Application

of Chariton for the relief of pain and the production of warmth; for

use on

patients with kidney problems, suffering from sciatica, paralysed and

those

affected by stiffness.

14d.

Hippiatr. Berol. 78

ἄλλη

μηλίνη χρυσῆ, ποιοῦσα πρὸς νεῦρα, πρὸς ἄρθρα, πρὸς ψυγμόν.

"Another

remedy, made of

quinces, a golden one; for use on muscles, joints and against

stiffness."

15.

Suda 1085 Adler s.v. μινθώσομεν. See also Schol. in Ar. Plut. 313

(...)

ἐπειδὰν δὲ οἱ τράγοι

ψυγμῷ περιπέσωσιν, εἰώθασιν οἱ αἰπόλοι λαμβάνειν τὴν κόπρον αὐτῶν καὶ

χρίειν

αὐτῶν τοὺς μυκτῆρας καὶ οὕτω τῇ δυσωδίᾳ πταρμὸν κινεῖν· τούτῳ δὲ τῷ

τρόπῳ λύειν

τὸ πάθος· ὁ γὰρ πταρμὸς θεραπεύει τὸ πάθος. (...)

When

the

billy-goats fall ill with a chill, the goat-shepherds have the habit of

taking

their dung and smear their nostril to incite sneezing because of the

malodour.

In this way they treat the affection. For sneezing heals this affection.

16.

Sch. GKd

in Nic. Ther. 43 Crugnola

(a.) <μελανθείου>

(...)

ἔστι δὲ καὶ πόα δυναμένη ψυγμὸν ἀπελάσαι, εἴ τις τρίψας τρὶς προσενέγκῃ

τῇ ῥινί

Black cumin (melanthion) is a plant which has the power to dispel the chill, if one pounds it and applies it thrice to the nose.

| 1.

|

[show] |

The word describes pathological states characterised by a feeling of extreme cold, freezing and/or rigour. Its witnesses fall into two distinct, though related, groups as regards the symptomatology. The first group encompasses descriptions which suggest that the patient experiences an inner chill or cold fit, often accompanied with a sensation of faintness and feebleness. Illustrative is the papyrus letter P.Oxy. LXXIII 4959.4-5 (datable on paleographical grounds in the second century) [5]. The author describes a passing fit of malaise experienced by his brother as psygmos “arising deep within” and couples it with a generalised feeling of faintness (ψυγμῶι ληφθεὶς ἐκ | βάθους καὶ ἐκλύ̣σει τοῦ σώματος). That a profound chill lies in the core of the condition is indicated by the writer’s later statement that following a complete recovery the brother was able to enjoy a bath in that very same day. Also Vettius Valens speaks of “internal discomforts” in a breath with psygmoi [9]. The status of the condition in contemporary medical lore is revealed by Galen when he discusses the use of oil and its effect as a therapeutic agent [6]. Galen reminds his readers that some bodies have a greater natural tendency towards freezing, manifested in the conditions “nowadays called psygmoi by people in common usage” (ἐν τοῖς καλουμένοις ἤδη συνήθως ὑπὸ πάντων ἀνθρώπων ψυγμοῖς). His formulation reveals the status of the term from a discursive and scientific point of view. That the term reflects common usage and is not a medical technical term is indirectly confirmed by its occurrence in two papyrus letters [4, 5] where lay individuals speak of their own or somebody else’s state of health, while its labelling by Galen as diathesis (ἐν δὴ ταῖς τοιαύταις διαθέσεσιν ...) implies that it did not savour the status of a disease proper but rather of a make-up, a condition of the body at a given time {Note that also the author of P.Oxy.Hels. 46 speaks of recovery from “ailment and a great cold”, perhaps drawing a certain line between the two states}.

The malaise is located in the region of the chest by one witness [1], while coughing and fever are the symptoms more often mentioned in conjuction with it [1, 9, 11]. Ignoring the early signs of the condition could result in among others pleurisy and lung inflammation, warns ps.Diocles. The compound ψυγμοκατάρρους, occuring only in Cyranides (II 15), points to runny nose being another main symptom, as do the passages concerning treatments for animals and humans [14a, 15, 16]. Shivering and sweating also belong to the most frequently mentioned symptoms [1, 2, 10]. It is significant that Pollux [8] intertwines this word family with that of φρίκη (“shuddering”, shivering”) and ῥῖγος (”shivering fit”), perharps in an attempt to discern in existing vocabulary different forms and grades of shivering. Shivering may affect the hands and arms when the condition is located in the chest [1, 10], or may be manifested as generalised chill and shivering due to venomous bites [2]. The feeling of faintness and feebleness overcoming patients in this state, mentioned by the author of P.Oxy. 4959 [5], is also confirmed by ps.Arist. Probl. 862b.2ff., a passage claiming that ailments occur more often in (the beginning of?) the summer when the human bodies are loose, frozen and feeble (ἐν δὲ τῷ θέρει, μανοῦ καὶ κατεψυγμένου παντὸς τοῦ σώματος καὶ ἐκλελυμένου πρὸς τοὺς πόνους ὄντος, ἀρχὰς νόσων ἀνάγκη πλείους μὲν γίνεσθαι ...). Also Plutarch (Quaest. Conv. 625 A-B) in a contribution to the discussion why elderly persons have the habit of drinking unmixed wine refers to ongoing discussions about the system in elderly persons being “frozen”, “hard to warm”, “loose” and “feeble” (κατεψυγμένην τὴν ἕξιν αὐτῶν καὶ δυσεκθέρμαντον οὖσαν ... αἰτία δ’ ἡ τῆς ἕξεως ἄνεσις• ἐκλυομένη γὰρ καὶ ἀτονοῦσα ...). The key-words are the same as in the medical passages associating psygmos and the sensation of faintness.

The information concerning the treatment of persons affected by the condition is neither abundant not very accurate. The testimonies point to remedies with warming properties and effect: application of oil is mentioned by Galen [6] and Rufus/ Oribasius [3/12]. The former does not appear to consider oil a very efficient remedy, while the latter seems to believe that oil boiled with rue, cumin, dill or laurel could alleviate the condition. The Hippiatrica Parisina recommend pounded cabbage in combination with garum and oil [14a], while the Hippiatrica Cantabrigiensia recommend the use of a remedy to be administered through the nose made from the flower of Lawsonia inermis (henna), and in general the use of warming and relaxing unguents [14b]. Other remedies contain milk and pepper or milk and sesame. Dioscorides (III 81) recommends a remedy prepared with the plant σαγάπηνον (Ferula communis {André Les noms de plantes ... 223, s.v. sacopenium}), while the scholiast of Nicander’s Theriaca suggests inhalation of melathion (Nigella sativa {André Les noms de plantes ... 157, s.v. melanthion}, black cummin) [16]. To relieve psygmos as a result of venomous bites Dioscorides recommends the use of warm sea-water, presumably on the biten spot [2]. A curious piece of information, provided by Suda and the scholiast of Aritophanes’ Wealth [15], pertains to the treatment of billy-goats suffering from the condition: the shepherds seek to induce sneezing – no doubt to open up the nose – by applying excrement to the nostrils.

A second, less prominent, group of sources point to an external manifestation of the condition. Its tenor is that a limp or an area in the body is so enfeebled as to be described as frozen stiff. The condition verges on paralysis with which it is mentioned in a breath as early as Dioscorides (III 73) who advertises the warming effect of the pyrethros on “frozen stiff and weakened parts of the body” (ἐψυγμένα καὶ παρειμένα μέρη τοῦ σώματος). Some of the other remedies administered to ease the condition are also recommended for paralysis or weakened limps. Drawing on (Hygieinus?) Hipparchus – a health expert known to Heras of Cappadocia – Galen advises preparing a remedy of pepperwort (Lepidium graminifolium {André Les noms de plantes ... 130, s.v. iberis}) and pig’s fat and applying it “on the aching part”when treating sciatica and psygmoi [7]. The description itself and the wider context (the recipe follows the exposition of how Damocrates used pepperwort to treat among others sciatica and different forms of paralysis) suggests an emollient for muscular conditions. More informative is a passage from a sermon of ps.Macarius in which he speaks of persons without visible wounds but who terrible stiffness impedes seriously to carry out manual work [13]. Muscular complaints, presumably common in pack animals, are indicated by the heading of the recipes in Hippiatr. Paris. 837 and Hippiatr. Berol. 1030 [14c, 14d].

| 2. | [show] |

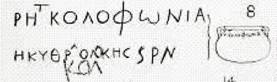

A dipinto inscription of the Roman period from Hawara, SB XVIII 13646, is particularly noteworthy. The dipinto is painted on the wide short slightly concave neck of an earthen container with two little handles set opposite each other. The vase and the inscription as a whole make possible to recover the connection – too often lost – between res and verbum, concretely confirming the shape of the container. Furthermore, the dimension of the inscription in itself compared to the surface of the vessel gives the idea of the small dimension of the object. The only available image of it is a drawing reproduction in PETRIE 1911, Pl. XXIV, no. 8[39].

The text is ῥητ(ίνα) κολοφώνια, ἡ κύθρα ὁλκῆς (δραχμῶν) ρν | κολο( ), «Kolophonian resin, the pot weight 150 drachmae». In this case the pot is used for the transport and the storage of a product, as often in papyrological sources[40]. The κολοφώνια ῥητίνη is a valuable resin exported from the Lydian city of Colophon which was frequently employed in the preparation of therapeutic remedies, especially soothing ones. Many mentions of it occur in the authors of materia medica, as well as in some medical papyrus, such as P.Grenf. I 52r,7 and v,9a and 10 [MP3 2396; LDAB 5432] of the III century CE, in the prescription for a malagma[41].

Another dipinto contains the word χύτρα. It is a cursive inscription on a Hellenistic coarse-ware pot found at Corinth (Corinth C 48-65, Deposit 110). The text, in two lines, partly obscured, has been tentatively read χωρεῖ ὄγκος τῆς χύτρας | κιννάβαριν μνᾶς τριάκοντα, «the capacity of this chytra (is such that) it holds 30 mnas’ worth of cinnabar»[42]. The vessel was a foreign import to Corinth, so the inscription was likely put on it at the unknown place from which it was exported[43]. The content it refers to, the cinnabar, is a type of red mercury ore from which the color vermillion is obtained. As a matter of fact, spectrographic analysis of scrapings from it showed the actual presence of a mercury compound, although there was no lump of cinnabar[44]. The archaeological context where the object was found, one of the thirty-one wells (Well XIX) which supplied water to the shops of the South Stoa at Corinth, contained an impressive amount of material used in connection with pigments, such as pottery still stained on the interior with color, but also iron spikes, tacks and bronze nails. Thus, it has been supposed that it was a «supply shop», a «store where paints, nails and associated materials for house construction and decoration are on sale»[45]. The cinnabar was actually used to create a red paint for decorative purpose in ancient times, but it was also employed in medicine (cf. Plin. Nat. XXX 116,5-6 illa cinnabaris antidotis medicamentisque utilissima est) and as a cosmetic pigment by women[46]. In alternative, as a mere hypothesis, being Corinth the city of the temple of Aphrodite where the sacred prostitution was practiced, might one speculate on a possible cosmetic destination for the cinnabar of this χύτρα? The images below are taken from WEINBERG 1949, Pl. 16,16 right and 16,15 (detail).

Finally, not only the χύτραι used to store and transport aromata and medicamenta were small-sized, but very likely also the ones involved in the preparation of remedies. Many miniature chytrai have been supplied by archeological excavations. These miniatures, employed only occasionally for domestic purpose (as indicated by exemplars blackened from use), were more often associated with burials or sacrificial pyres. They otherwise served as perfume-pots[47]. Several specimina from the Athenian Agora are representative, like for instance P 24864 (H. 6 cm x Diam. 9 cm)[48], P 19845 (H. 3,7 cm x 4,8 cm)[49] and P 7429 (H. 3,1 cm x 4,3 cm)[50]. Chytridia of this kind were probably suitable even in medical context, especially in case of prescriptions for individual use.

| 1.

Lexicon entries |

[show] |

Chantraine 1968, 1295-96 s.v. ψυχρός

| 2. Secondary literature | [show] |

Anastasia Maravela